Evolution of “Merchandising Rights”

WikiMili recently published the updated list of the most lucrative IPs in the world. “Pokémon” which gained a total of about 100 billion dollars is still ranked the first. “Glory of Kings”, the first Chinese IP that appeared in the top 50 of the list gained a total of about 9.97 billion US dollars. Here is the first group (total earnings of over 50 billion dollars) on the list.

| Title | Year of creation | Total earnings (US dollars) | Breakdown of earnings (estimates) | Original media | Creator | Persons entitled |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| over 50 billion dollars | ||||||

| Pokemon | 1996 | 100 billion | licensed derivative products-76 billion | electronic games | Satoshi Tajiri and Sugimori Ken | Trademark: NintendoCopyright: Pokemon(Nintendo, Game Freak, Creatures) |

| electronic games-over 22.716 billion | ||||||

| cinema tckets-1.838 billion | ||||||

| home recreation-144.4 million | ||||||

| books on walkthroughs-142 million | ||||||

| jet planes-30 million | ||||||

| Hello Kitty | 1974 | 84.5 billion | derivative products-84.515 billion | images of cartoon characters | Yuko Shimizu and Tsuji Shintarou | Sanrio |

| Winnie the Pooh | 1924 | 80.3 billion | retail sales-79.823 billion | books | A.A.Milne and E.H.Shepard | Walt Disney Ltd. |

| cinema tckets-460 million | ||||||

| DVD and blue-ray discs-64 million | ||||||

| Mickey Mouse and his friends | 1928 | 80.3 billion | retail sales-79.5331 billion | animations | Walt Disney and UB Iwerks | Walt Disney Ltd. |

| cinema tickets-457.4 million | ||||||

| home theatre-293 million | ||||||

| Star Wars | 1977 | 68.7 billion | derivative products-42.217 billion | movies | George Lucas | Lucas Film Ltd. (Walt Disney Ltd.) |

| cinema tickets-10.316 billion | ||||||

| home theatre-9.071 billion | ||||||

| games-5.01 billion | ||||||

| books-1.82 billion | ||||||

| TV-280 million | ||||||

(Source: List of highest-grossing media franchises, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_highest-grossing_media_franchises)

It is apparent that earnings of these IP operators mainly sourced from derivative products and retail sales. According to an analysis by “San Wen Yu”, a wechat public account name, half in the top 50 IPs gained most earnings from derivative products and retail sales, which account for 52% of total earnings. (Source: World Top 50 Lucrative IPs: Top 1 with Earnings of 100 Billion US Dollars, of Which 76 Billion Comes from Licensed Derivative Products, by “San Wen Yu”, a public wechat account name).

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/Zv8Jhw3dNvdsY0eZf3TKKA

Almost all earnings of “Glory of King” ranked in the 50th place came from games.

Derivative and retail products (which may be called licensed merchandise, merchandise sales or retail sales or in other way in information from different sources), from which international IP giants gained most earnings refer to “merchandising right license” in IP operation contracts, especially international ones. A merchandising right license for an IP is granted on the basis of “merchandising rights” in the IP. Now let’s discuss how “merchandising rights” evolved in China, which international IP giants are skilled at using its magic to make profits.

I. What are merchandising rights?

The literal meaning of “merchandising” seems to “make things that are not products into products”. In some cases, for example, for garage kits of Luffy in One Piece, it is very apt, while in other common cases, it is quite confusing.

For example, does merchandising the Avengers by printing their images on T-shirts which are products mean making the animation characters into products? More apparently, explaining merchandising cases of using the Bald Guy in advertising or appearing as the Happy Goat at opening ceremonies of shopping malls in that way seems not to make sense.

Actually, the Chinese translation of “merchandising right”, by all accounts, was invented by Japanese people in the 1960s when a Japanese TV station entered into an animation broadcast contract with a US business. The translation was accepted by the Chinese legal profession. The literal translation of “merchandising” is “promoting products”. For example, “merchandising” animation characters means using them to promote or increase sales of products (including services, as below). The above “merchandising” cases, if in this meaning, all make sense.

In a WIPO report in 1994 the definition of “character merchandising” is the person with rights in an image (or licensee, as below) uses basic personality features of the image in connection with products and uses the image to attract customers and arouse potential customers’ desire to buy products. This definition can prevent us from being misled by the Chinese translation of “merchandising rights” and help us clearly understand its nature.

Virtual images like animation characters, real people and elements like their names, images, portraits and sound can be merchandised.

If we are familiar with the nature and cases of “merchandising rights”, we will understand that merchandising rights in a virtual image are basically covered by copyrights in the same image and merchandising rights in a real person’s image are actually the person’s portrait rights and the same is true for a registered trademark of a person’s name and a patent on an appearance design. A work title or a person’s name that could not be or is not registered as a trademark or is too short to be considered as creative and protectable under copyright law, if well-known enough and misused (as the title of the popular internet drama Surprise used as the title of an entertainment show), is protectable under law against unfair competition.

What status “merchandising rights” are accounted in the legal system of our country?

II. Introduction of “merchandising rights” in China

Our research shows the term “merchandising rights” was first used by the Chinese legal profession to discuss who had rights in the image of “Mad Monk” in the TV drama series Mad Monk produced in 1986.

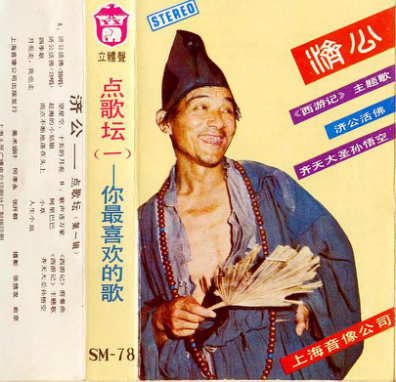

In the 1980s Shanghai Audio & Video Ltd. released pop song albums on cassette titled “Pop Music-Your Favorite Songs”. The first album contained theme songs and background songs of popular TV series such as Journey to the West and Mad Monk and was accommodated on a cassette with a cover like this.

The TV series Mad Monk aroused national interest in TV and films and was a miracle in the TV history. You Benchang, who acted Mad Monk so well that people of all ages knew him, filed with the department in charge of audio and video products a complaint that his portrait rights was infringed. The final decision was that it was portrait right infringement.

The decision was controversial in the legal profession. Did rights in the image of “Mad Monk” belong to actors or the cast?

People who took part in the discussion found it difficult to deal with this issue only based on portrait rights and copyrights and then introduced the term “merchandising rights in characters”. At that time “merchandising rights” were described as “rights to use characters in works as product marks”.

In the following twenty years or so, “merchandising rights” were widely discussed in the Chinese legal profession. Professors Zheng Chengsi and Wu Handong, authorities on intellectual property rights joined the discussion and advanced the term “image rights”, which they thought were a type of independent property rights between personal rights and copyrights and on the borderland between trademark, business name and goodwill rights and copyrights.

The professor Liu Yinliang said, as we stated above, “merchandising rights”, which were misunderstood because of its translation, actually meant using characters for promotional purposes and for lack of a solid legal basis on which “merchandising rights” could exist as independent rights, it is all right to apply existing laws including Law Against Unfair Competition to related rights.

III. Merchandising rights” in legal practice of our country

The academia put forward the term “merchandising rights”. How did courts respond to it? As we know, merchandising right disputes are most common in administrative cases relating to trademarks.

It is always very common that titles and character names of literature and art works are registered as trademarks by people who have no rights in these works, making it very difficult to develop derivative products of the works. In the Trademark Law, if a registered trademark “damages prior rights”, the entitled person can request for the invalidity of the trademark. However, can we call work titles or character names prior rights?

From the “007 Bond” case in 2011 to the “Teambeattles” case in 2015, courts seemed open to “merchandising rights”. In the “007 Bond” case, reasons for protecting character names given by the court were their popularity and creativity and commercial value and opportunities obtained by the entitled person spending huge amounts of work and money.

In the “Teambeatles” case, the court clearly stated that the title of a famous band had “an appeal that could attract potential customers and increase sales and business opportunities” and such “potential business opportunities and benefits were merchandising rights in the band title”, which should be protected by law although they were not a type of statutory rights and more aptly called “merchandising interests”.

In both cases, the courts mentioned the term “merchandising rights” exactly and decided to announce the invalidity of the trademarks on the same ground of “damage to prior rights”.

The situation seemed to change when the case of “The Basketball Which Kuroku Plays” was decided in 2016. In this case, the applicant for the invalidity of the trademark claimed that the trademark registration “damaged its merchandising rights in virtual characters”. The Beijing Intellectual Property Court allowed that “The Basketball Which Kuroku Plays” was well-known in China and held that attempts to register the trademark “The Basketball Which Kuroku Plays” were acts of seeking illegal profits.

There would be no entitled person with prior rights or interests that could prevent such acts of trademark registration, especially when work titles and character names could not constitute prior rights. As a result, this kind of misconduct could not be effectively controlled. If such acts are treated as acts of seeking illegal profits in other way, people with relevant interests would no longer be left unprotected.

The court decided that the trademark was invalid because approval for the trademark registration was obtained in “other illegal way”. The decision in this case was the same as that in previous two cases, but this time the court did not allow merchandising rights to be prior rights.

The court made the decision in an indirect way perhaps because they were afraid of being criticized for “doing the job of creating statutory rights which should be done by the legislative authority. Anyway, they protected merchandising interests although not admitting they were a type of “rights”.

Please note that the time limit on filing a request for the invalidity of a trademark on the ground of “damage to prior rights” is five years. No such a request is acceptable after five years. However, there is no time limit on filing the same request on the ground of “obtaining approval for registration in other illegal way”. The result of this indirect approach shows the protection is strengthened, not weakened. However, statutory and non-statutory prior rights are not protected in a balanced way.

IV. Are merchandising rights a type of statutory rights?

Article 22.2 of the Legal Interpretation of the Rules on Several Issues Concerning Hearings of Administrative Cases Brought for Recognition of Licenses for Trademark Rights (“Rules” effective from 1 March 2017) by the Supreme People’s Court in January 2017 provides that “within the period of time when copyright to a work is protectable, if a relevant person claims prior rights to the title of the work or name of a character in the work that is well-known and used as a trademark on products in a way that could cause relevant public to mistakenly believe such use is permitted by or connected with the entitled person, the court should allow it”.

As that issue seemed to be finally resolved, a lot of professionals believed merchandising rights were not a type of rights created by lawmakers, but were accepted by courts as protectable interests.

Not long after Rules was taken into action, Beijing High Court explained and clarified this issue in the “Sunflower Bible” case.

In this case, the court held “Sunflower Bible” was the name of a fiction work in another work, not a work title or a character name, refused to allow prior rights in it and rejected the request for announcement of the invalidity of the “Sunflower Bible” trademark.

This appears to give a definition of merchandising rights that could be protected in the way as prior rights. In strict accordance with Rules, prior rights depend on the title of a well-known work and the name of a character in the work. The verdict stated with reasons that even in titles and character names of well-known works no new civil rights or interests would be created beyond the boundaries of existing law.

This verdict seriously stated “it only dealt with the issue of whether the trademark registration in dispute violated the trademark law considering arguments for “merchandising rights” made by the Perfect World Ltd. and does not make a comprehensive decision on whether the trademark registration in dispute infringed all prior rights or interests claimed by the Perfect World Ltd. or reflexible interests arising from attempts to prevent unfair competition under the law against unfair competition”.

Does this verdict mean to “deny having said the “Sunflower Bible” trademark was invalid or prior interests in the title “Sunflower Bible” are not protectable and explain that the “merchandising rights” are not a new type of rights beyond the boundaries of existing law and the trademark examination committee should make a comprehensive assessment from the angle of the law against unfair competition, not only finding the trademark was invalid on the ground of “merchandising rights”.

The legal profession of our country hasn’t accounted a definite “status” to merchandising rights. However, it is apparent from the above verdicts that courts at least agree to protect this kind of interests, which actually, in the current legal system of our country, could be protected under the Law Against Unfair Competition without no need to create a new right.

Based on the above, the five-year restriction may not apply to applications for announcement of the invalidity of a trademark. It seems that we don’t need to study more about whether “merchandising rights” are a type of statutory rights.

沪公网安备 31010602001694号

沪公网安备 31010602001694号